What Is An Endogenous Retrovirus (ERV)?

A retrovirus is an RNA virus, the genome of which is reverse transcribed into DNA inside a host cell, using an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. The DNA then becomes incorporated into the genome of the host organism, using another enzyme called integrase. Retroviruses belong to the viral family Retroviridae, and are enveloped viruses — meaning they possess viral envelopes, typically composed of proteins and phospholipids, covering their protein capsids. Viral envelopes also contain some viral glycoproteins which assist in its access to the interior of the host cell. Glycoproteins on the surface of the envelope identify and bind to receptor sites on the membrane of the host cell, facilitating fusion of the host’s membrane and the viral envelope. This, in turn, allows the entry of the viral genome and capsid into the host cell’s interior.

An endogenous retrovirus is a special kind of retrovirus which invades the germline and thus becomes inherited by the organism’s progeny and subsequent future generations. Once the retrovirus has undergone reverse transcription in the cytoplasm and integrated into the host organism’s genome, the retroviral DNA is referred to as a “provirus”. The virus then undergoes the normal processes of transcription and translation in order to express the viral genes.

Retroviral Structure

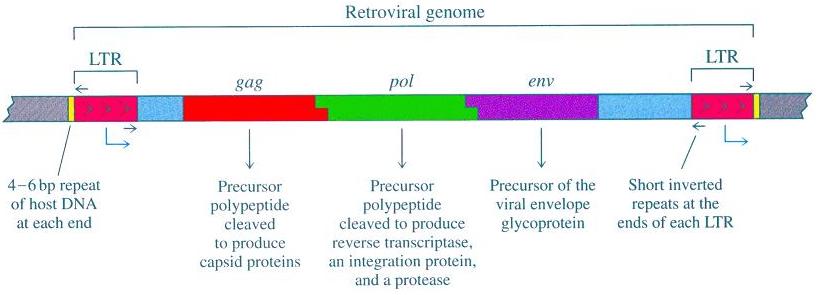

As you can see from the accompanying diagram [source], there are three significant protein-coding genes associated with the retroviral genome: gag; pol; and env. These genes encode for viral proteins including the viral matrix, capsid, nucleoproteins, reverse transcriptase, integrase, and the envelope protein. Gag proteins are major components of the viral capsid (present in about two to four thousand copies per virion). The protein Protease functions in proteolytic cleavage to produce mature gag and pol proteins. The pol proteins are basically responsible for the synthesis of viral DNA and subsequent insertion into the genome of the host following infection. The env proteins play a part in the entry of the virion into the host cell’s interior.

In addition to gag, pol and env, retroviruses are characterized by the 5′ and 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences. These LTR sequences can be thought of as the control center for gene expression. Retroviruses have somewhat typical eukaryotic promoters with transcriptional enhancers. Some, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), even have regulatory elements which are responsive to either viral or specialized cellular (e.g. hormonal) trans-activating factors.

All of the requisite signals for gene expression (i.e. enhancer, promoter, transcription initiation, transcription terminator and polyadenylation signal) are found in the LTR sequences. The LTRs each contain two unique non-protein-coding sequences, called U5 (at the 5′ end) and U3 (at the 3′ end), which are responsible for encoding particular controlling elements. The enhancer and other transcription regulatory signals are contained in the U3 region (which is at the 3′ end) of the 5′ LTR. Approximately 25 bp from the start of the LTR sequence the promoter TATA box is located. And thus the 5′ LTR operates as a promoter for RNA polymerase II. In contrast, the 3′ LTR does not ordinarily serve as a promoter, but rather acts in transcription termination and polyadenylation. But when the 5′ LTR is compromised or its integrity is disrupted, the 3′ LTR can serve as a promoter.

How Do Retroviruses Integrate Themselves Into A Host’s Genome?

In order to better visualize how these retroviruses are able to infect their host organism, the following animation will be helpful:

Are ERVs Genuine Inserts? Or Are They Intrinsic Genetic Elements?

This is a question with some justification for subscribing to either of the above views. It is clear that, for an ERV insert to be retained by progeny, the retrovirus must infect the germ cells. And, indeed, it has been documented that the germline is a target for retroviruses SIV and SHIV in juvenile macaques. Moreover, these elements certainly look strikingly like retroviral elements. For example, they possess the three markedly retroviral genes discussed previously. Some ID proponents have argued that, in spite of this striking appearance, the structure of the germ-cell production system makes it extremely unlikely that the inserts were accomplished by viruses, and thus these hitherto-thought-to-be ERV sequences are not, in fact, viral in origin at all. This is an interesting argument. It does seem somewhat unlikely that retroviral elements would be able to insert themselves literally hundreds of thousands of times into the germ cells without causing fatalistic damage to the host organism. Moreover, it seems far more likely than not that a virally-infected sperm cell would be substantially less fit and hence out-competed in the race to the egg. And the process of apoptosis (programmed cell death) would be likely to eliminate virally-infected sex cells. While such a successful germline insertion might be inherited under very rare circumstances, its occurrence literally hundreds of thousands of times seems highly unlikely. Moreover, the alternative hypothesis which has been offered by some is that retroviruses themselves might have their origin as conventional genomic components (e.g. Greenwood et al. 2004). Only time will tell if there is any substance to this suggestion.

On the flip side of the coin, as a consequence of the repair by the host cell’s DNA repair proteins of single-strand gaps at each end of the inserted sequence formed upon element insertion, an integration is marked and characterised by a duplication of the target site. On this basis, some would argue that these sequences are, indeed, inserts. Conversely, Paprotka et al. (2011) recently reported on the origin of the retrovirus XMRV as the result of a unique recombination event involving two proviruses. This is an interesting finding. As it happens, the two provirus DNA sequences which combined to become the novel retrovirus were situated on the chromosome right where they could be joined by the precise cellular recombination machinery. This opens up all sorts of interesting possibilities from a design perspective. But we need not go there just now.

Are ERVs Functional?

Over the last decade or two, a myriad of different functions have been identified for components of ERVs. For example, the long terminal repeats (LTRs), which occur at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the retroviral sequence, are known to contribute to the host organism’s promoters (Dunn et al., 2005). Conley et al. (2008) also report that,

Our analysis revealed that retroviral sequences in the human genome encode tens-of-thousands of active promoters; transcribed ERV sequences correspond to 1.16% of the human genome sequence and PET tags that capture transcripts initiated from ERVs cover 22.4% of the genome. These data suggest that ERVs may regulate human transcription on a large scale.Indeed, ERV LTRs have even helped to shape the tumour-suppressor protein, p53 (aka the “guardian-of-the-genome”), as documented by Wang et al. (2007).

Kigami et al. (2003) also report that MuERV-L is one of the earliest transcribed genes in mouse one-cell embryos. In fact, knocking out the sequence’s expression causes embryogenesis to grind to a halt at the four-cell stage.

There is also now a growing wealth of literature documenting the role of ERVs in conferring immunity to their host from infection by exogenous retroviruses (see, for example, Malik and Henikoff, 2005).

One particularly remarkable incidence of functionality with regards these sequences is the involvement of the highly fusogenic retroviral envelope proteins (the syncytins) which are known to be crucially involved in the formation of the placenta syncytiotrophoblast layer generated by trophoblast cell fusion. These proteins are absolutely critical for placental development in humans and mice. The different kinds of Syncytin protein are called “syncytin-A” and “syncytin-B” (found in mice); “syncytin-1″ and “syncytin-2″ (found in humans). But here’s the remarkable thing: Although serving exactly the same function, syncytin-A and syncytin-B are not related to syncytin-1 and syncytin-2. Syncytin protein also plays the same function in rabbits (syncytin-ory1). But rabbit syncytin is not related to either the mouse or the human form. These ERVs are not even on the same chromosome. Syncytin-1 is on chromosome 7; syncytin-2 is on chromosome 6; syncytin-A is on chromosome 5; and syncytin-B is on chromosome 14.

Indeed, Dupressoir et al. (2005) report that

Together, these data strongly argue for a critical role of syncytin-A and -B in murine syncytiotrophoblast formation, thus unraveling a rather unique situation where two pairs of endogenous retroviruses, independently acquired by the primate and rodent lineages, would have been positively selected for a convergent physiological role. [emphasis added]This is a remarkable case of convergent evolution, of a kind which is highly unlikely to have occurred by Darwinian means.

Shared ERVs And Primate Common Ancestry

There are at least two points which are worthy of remark here. First, isn’t it interesting that Darwinists have developed a kind of “complexity-specification-criterion” of their own? Because of the sheer improbability (it is alleged) of a retrovirus integrating itself into the same locus with the same orientation in multiple independent lineages, it is thought that this constitutes evidence for common ancestry — under the principle of parsimony. Where improbability and pattern specificity converge, ID proponents argue that design is the best explanation for the given phenomenon. Deep down, Darwinists know this to be the case — which is why they assert that the germline insertion only happened once and was hence passed on to the host’s progeny.

The second point worthy of note is that it shouldn’t surprise us that ERV elements can be found occupying the same genetic loci across multiple taxa. This is indicative of the specificity of the target site preference. Such target sites might exist by virtue of the fact that they are most conducive to their successful reproduction (e.g. the necessitude for expression of the ERV’s regulatory elements; the activity of the host’s DNA correction system, etc). Mitchell et al. (2004) suggest “that virus-specific binding of integration complexes to chromatin features likely guides site selection.”

A couple of years ago, while I was still a lowly biology undergraduate student and well before I entered into the world of ID, I asked evolutionary biologist Richard Sternberg about his take on the ERV question. He wrote back to me,

Now, the story that these seemingly defunct retroviruses provide compelling evidence for common descent on the one hand, and support for the notion of non-designed junk on the other, is based on an interpretation that is almost thirty years old and contradicted by recent data. For one thing, ERVs are markedly taxon-specific and they all have non-random chromosomal distributions. The mouse and rat have different ERV families and yet many of them occupy similar genomic sites. This is explained by the insertion machineries having preferences for specific DNA targets or chromatin profiles. So while one can find some retroviral sequences occupying a position shared between by two species, it cannot be ruled out that such similarity is due to constraints on integration. In yeast, for example, the ERV Ty repeatedly inserts into the promoters of transfer RNA genes. And human and mouse “jumping genes” such as Alu and B1/B2, respectively, are not homologous and yet thay have the same linear pattern of placement. Such genomic profiles look like inherited accidents from afar but close inspection reveals that they are independent events. Appearances can be deceiving.

[...]

I could continue in this vein for some time. My point is that a tenebrific spin has been given to ERVs by the Darwinians. The spin works only as long as one superficially reviews old literature. But it dissipates as soon as one delves into the weath of data that we now have available to us.In 2001, Barbulescu et al. identified ten different HERV-Ks in the human genome. Eight of them were unique to the human genome. A ninth HERV-K was detected in the human, chimpanzee, bonobo and gorilla genomes, but not in the orang-utan genome. The tenth was found in humans, chimpanzees and bonobos. They also reported,

We identified a human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) provirus that is present at the orthologous position in the gorilla and chimpanzee genomes, but not in the human genome. Humans contain an intact preintegration site at this locus. These observations provide very strong evidence that, for some fraction of the genome, chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas are more closely related to each other than they are to humans. [emphasis added]It seems that the most plausible explanation for this is an independent insert in the gorilla and chimpanzee lineages. Notice that the intact preintegration site at the pertinent locus in humans precludes the possibility of the HERV-K provirus having been inserted into the genome of the common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas, and subsequently lost from the human genome by processes of genetic recombination. Though there are other possible candidate hypotheses for this observation (such as incomplete lineage sorting), in the context of other indications of locus-specific site preference, this data is, at the very least, suggestive that these inserts may in fact be independent events.

But there’s more.

Another study, by Sverdlov (1998) reports,

But although this concept of retrovirus selectivity is currently prevailing, practically all genomic regions were reported to be used as primary integration targets, however, with different preferences. There were identified ‘hot spots’ containing integration sites used up to 280 times more frequently than predicted mathematically. [emphasis added]I could continue in a similar vein for some time. Other classes of retroelement also show fairly specific target-site preferences. For example, Levy et al. (2009) report that Alu retroelements routinely preferentially insert into certain classes of already-present transposable elements, and do so with a specific orientation and at specific locations within the mobile element sequence. Moreover, a study published in Science by Li et al.(2009) found that, in the waterflea genome, introns routinely insert into the same loci, leading the internationally-acclaimed evolutionary biologist Michael Lynch to note,

Remarkably, we have found many cases of parallel intron gains at essentially the same sites in independent genotypes. This strongly argues against the common assumption that when two species share introns at the same site, it is always due to inheritance from a common ancestor.A recent study by Spradling et al. (2011) documented Drosophila P elements preferentially transpose to replication origins. They report,

P element insertions preferentially target the promoters of a subset of genes, but why these sites are hotspots remains unknown. We show that P elements selectively target sites that in tissue-culture cells bind origin recognition complex proteins and function as replication origins.Finally, Daniels and Deininger (1985) suggest that,

…a common mechanism exists for the insertion of many repetitive DNA families into new genomic sites. A modified mechanism for site-specific integration of primate repetitive DNA sequences is provided which requires insertion into dA-rich sequences in the genome. This model is consistent with the observed relationship between galago Type II subfamilies suggesting that they have arisen not by mere mutation but by independent integration events.Such target-site preferences are also documented by Cereseto and Giacca (2004), Mitchell et al. (2004), and Bushman (2003).

What About Shared Mutations in ERVs?

Regarding shared “mistakes” between primate genomes, this argument again assumes that mutations are random and are unlikely to occur convergently. Cuevas et al. (2002), however, have documented, in retroviruses, the occurrence of molecular convergenes in 12 variable sites in independent lineages. Some of these convergent mutations even took place in intergenic regions (changes in which are normally thought to be selectively neutral) and also in synonymous sites. The authors also note that this observation is fairly widespread among HIV-1 virus clones in humans and in SHIV strains isolated from macaques, monkeys and humans.

As the authors note,

One of the most amazing features illustrated in Figure 1 is the large amount of evolutionary convergences observed among independent lineages. Twelve of the variable sites were shared by different lineages. More surprisingly, convergences also occurred within synonymous sites and intergenic regions. Evolutionary convergences during the adaptation of viral lineages under identical artificial environmental conditions have been described previously (Bull et al. 1997; Wichman et al. 1999; Fares et al. 2001). However, this phenomenon is observed not only in the laboratory. It is also a relatively widespread observation among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 clones isolated from patients treated with different antiviral drugs; parallel changes are frequent, often following a common order of appearance (Larder et al. 1991; Boucher et al. 1992; Kellam et al. 1994; Condra et al. 1996; Martinez-Picado et al. 2000). Subsequent substitutions may confer increasing levels of drug resistance or, alternatively, may compensate for deleterious pleiotropic effects of earlier mutations (Molla et al. 1996; Martinez-Picado et al. 1999; Nijhuis et al. 1999). Also, molecular convergences have been observed between chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses (strain SHIV-vpu+) isolated from pig-tailed macaques, rhesus monkeys, and humans after either chronic infections or rapid virus passage (Hofmann-Lehmann et al. 2002).I could cite several other similar studies. For another case example, see Bull et al. (1997), which documents that,

Replicate lineages of the bacteriophageWhat About LTR-LTR Divergence?X 174 adapted to growth at high temperature on either of two hosts exhibited high rates of identical, independent substitutions. Typically, a dozen or more substitutions accumulated in the 5.4-kilobase genome during propagation. Across the entire data set of nine lineages, 119 independent substitutions occurred at 68 nucleotide sites. Over half of these substitutions, accounting for one third of the sites, were identical with substitutions in other lineages. Some convergent substitutions were specific to the host used for phage propagation, but others occurred across both hosts. Continued adaptation of an evolved phage at high temperature, but on the other host, led to additional changes that included reversions of previous substitutions. Phylogenetic reconstruction using the complete genome sequence not only failed to recover the correct evolutionary history because of these convergent changes, but the true history was rejected as being a significantly inferior fit to the data. Replicate lineages subjected to similar environmental challenges showed similar rates of substitution and similar rates of fitness improvement across corresponding times of adaptation. Substitution rates and fitness improvements were higher during the initial period of adaptation than during a later period, except when the host was changed.

Darwinists sometimes argue that the degree of LTR-LTR divergence (in the context of the relative age of a given insertion) can be used as a predictive tool to demonstrate common ancestry. The argument goes that, because LTRs are thought to accumulate mutations at a roughly equivalent rate, LTRs which are highly divergent should correspond to an older integration, whilst LTRs which are less divergent should correspond to a younger insertion. The problem is that the pattern is nothing like as neat and tidy as Darwinists would like. Hughes and Coffin (2005) report that,

HERV elements make up a significant fraction of the human genome and, as interspersed repetitive elements, have the capacity to provide substrates for ectopic recombination and gene conversion events. To understand the extent to which these events occur and gain further insight into the complex evolutionary history of these elements in our genome, we undertook a phylogenetic study of the long terminal repeat sequences of 15 HERV-K(HML-2) elements in various primate species. This family of human endogenous retroviruses first entered the primate genome between 35 and 45 million years ago. Throughout primate evolution, these elements have undergone bursts of amplification. From this analysis, which is the largest-scale study of HERV sequence dynamics during primate evolution to date, we were able to detect intraelement gene conversion and recombination at five HERV-K loci. We also found evidence for replacement of an ancient element by another HERV-K provirus, apparently reflecting an occurrence of retroviral integration by homologous recombination. The high frequency of these events casts doubt on the accuracy of integration time estimates based only on divergence between retroelement LTRs. [emphasis added]Summary & Conclusion

In summary, the stupendous claim that there is overwhelming evidence that humans and chimpanzees have common ancestry is an overstatement. The arguments for common ancestry based upon shared ERV elements needs to be considered in the context of other evidence as well (such as that from embryology), which clearly militates against the paradigm of common descent. And then there is still the lack of any feasible naturalistic evolutionary mechanism which can account for the complexity of life. When all the facts are in, I am inclined to be very skeptical of not just the claims of neo-Darwinism to be able to explain all of life, but also that the observed molecular patterns are robust evidence for the common ancestry model. If it is the case, as has been suggested by some, that these HERVs are an integral part of the functional genome, then one might expect to discover species-specific commonality and discontinuity. And this is indeed the case.

Great Dr. imoloa herbal medicine is the perfect cure remedy for HIV Virus, I was diagnose of HIV for 8years, and everyday i am always on research looking for a perfect way to get rid of this terrible disease as i always knew that what we need for our health is right here on earth. So, on my search on the internet I saw some different testimony on how Dr. imoloa has been able to cure HIV with his powerful herbal medicine. I decided to contact this man, I contacted him for the herbal medicine which i received through DHL courier service. And he guided me on how to. I asked him for solutions a drink the herbal medicine for good two weeks. and then he instructed me to go for check up which i did. behold i was ( HIV NEGATIVE).Thank God for dr imoloa has use his powerful herbal medicine to cure me. he also has cure for diseases like: parkison disease, vaginal cancer, epilepsy, Anxiety Disorders, Autoimmune Disease, Back Pain, Back Sprain, Bipolar Disorder, Brain Tumour, Malignant, Bruxism, Bulimia, Cervical Disk Disease, cardiovascular disease, Neoplasms, chronic respiratory disease, mental and behavioural disorder, Cystic Fibrosis, Hypertension, Diabetes, asthma, Inflammatory autoimmune-mediated arthritis. chronic kidney disease, inflammatory joint disease, back pain, impotence, feta alcohol spectrum, Dysthymic Disorder, Eczema, skin cancer, tuberculosis, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, constipation, inflammatory bowel disease, bone cancer, lungs cancer, mouth ulcer, mouth cancer, body pain, fever, hepatitis A.B.C., syphilis, diarrhea, Huntington's Disease, back acne, Chronic renal failure, addison disease, Chronic Pain, Crohn's Disease, Cystic Fibrosis, Fibromyalgia, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, fungal nail disease, Lyme Disease, Celia disease, Lymphoma, Major Depression, Malignant Melanoma, Mania, Melorheostosis, Meniere's Disease, Mucopolysaccharidosis , Multiple Sclerosis, Muscular Dystrophy, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Alzheimer's Disease email- drimolaherbalmademedicine@gmail.com / call or {whatssapp ..... +2347081986098. }

ReplyDeleteI have an FAQ on ERVs which answers all the points in your article.

ReplyDeleteIt is @ https://barryhisblog.blogspot.com/p/endogenous-retroviruses-frequently.html

0. This looks hard. Do you have a simple introduction to the subject?

1. What is the "case for common descent" from ERVs?

2. Why do virologists and geneticists think that ERVs come from retroviruses? Isn't that just supposition on their part?

3. Isn't this just circular reasoning, assuming evolution to "prove" evolution?

4. How many ERVs are shared, in common locations, in the genomes of humans and chimps?

5. Don't retroviruses target particular locations in the DNA? Doesn't this explain corresponding ERVs?

6. ERVs do stuff. Doesn't that prove that they didn't originate from retroviruses, but were designed?

7. ERVs promote the transcription of host DNA. Doesn't this prove they are designed?

8. ERVs are essential in reproduction (syncytin and the formation of the placenta). How can this be?

9. Aren't the same ERV genetics in the same places in different species because they have to do the same job?

10. But how can you rule out design as an explanation?

11. How could a species survive a massive invasion of retroviruses into its genome?

12. How could ERVs survive programmed cell death (apoptosis)?

13. The same retrovirus or ERV has been found in two species that evolutionists say are very distantly related. How is this possible?

14. What if we find an ERV in a common location in chimpanzees and gorillas, but not in humans?

15. David DeWitt at AiG says ERVs do not line up with the expected evolutionary progression. What gives?

16. What's all this about the Phoenix Virus? Sounds like a Michael Crichton science fiction story!

17. Hasn't the evolutionist's story about ERVs been debunked by "scientists' such as Dr. Yingguang Liu and Dr. Georgia Purdom?

18. Could you have this backwards? Maybe retroviruses come from designed-in variation inducing genetic elements (VIGEs)?

Hello everyone on here, I want to share with you all a great testimony on how I was cured by Dr Jekawo, who cured so many diseases.

ReplyDeleteI was suffering from herpes and diabetes also my little sister was a victim of blood cancer too but with the help of Dr Jekawo we are all fine, well with his natural remedies that he prepare then send to us through dhl courier he then instruct us on how to drink the herbal medicines which we did and today we are completely well, we have being living free for 2 years now and it's seems like a God sent when I met him online by a lady giving testimony online like I'm doing right now.also I have introduce Dr Jekawo to several colleagues from works suffering from different kind of diseases and Dr Jekawo has healed all of them with his herbal knowledge. he's a great man with ancestral power to cure people with herpes,cancer,diabetes,hepatitis,hpv,lupus,als,hiv/aids, also spiritual consultation he's available for that as well.

I email him on: drjekawo@gmail.com whatsapp through +2347059818667. his website www.drjekawo.com because that's the only source to get to him as he lives far from the United state,I told him that I will be giving testimony on his behalf because he's a good man with a Godly heart.